Nelayan tradisional, salah satu profesi yang terpukul oleh pandemi Covid-19, khususnya nelayan tuna, yang hasil tangkapannya diekspor ke luar negeri. Kini mereka Hidup dengan megandalkan tabungan dan sebagian, bantuan pemerintah.

By May Rahmadi

“These days, they are restless because they have to lose their source of livelihood that keeps their family alive,” said thirty-five-year-old Salman Adam, who represented tuna fishermen in Ternate, North Moluccas in a rapid assessment report conducted by researchers of Masyarakat dan Perikanan Indonesia (MDPI) foundation. “Oh, Covid-19, be gone fast, we miss the normal tuna prices.”

On a normal day, Adam would set off to catch tuna at around four in the morning and only return to shore at around seven in the evening, but the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has now changed this habit.

Adam has ceased going to sea to fish since early March. Not because there are no tuna to catch, but because revenues from fishing could no longer offset operational costs. Persisting to fish now, would mean losing money.

“We no longer go out to fish. Fishing costs a lot, more than one million rupiah and just imagine that if we only get two or three fishes, that would not be able to cover our operational costs. That is why we just decided not to operate,” Adam told Ekuatorial on June 6, 2020.

Since Covid-19 turned into a global pandemic, many countries have adopted a lockdown policy and consequently export markets shut down. Exporters could no longer export tuna to the United States for example, one the major takers of Indonesian tuna.

The price of tuna plunged. “The price of tuna has fallen drastically, from Rp 45,000 per kilogram to just Rp 18,000 per kilogram in Ternate,” lamented Adam. “I no longer get revenue at all as the tuna we sell is usually exported to the United States and at present, that is not possible.”

The former Mission Director of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Indonesia, Erin E. McKee was quoted on the official website of the Ministry of Marine and Fishery Affairs, as saying in April of 2019, the United States was Indonesia’s top tuna export destination.

In 2016, for example, Indonesia exported 1.2 million metric tons of tuna to the United States and in the following year, the United States imported $1 billion worth of Indonesian tuna.

Prior to the eruption of the pandemic, when fish prices and demands were still normal, Adam could make on average Rp 1.1 million from every fishing trip, before deduction of operational costs.

But because it no longer make any sense to operate, Adam no longer has a reliable income and has to rely on his savings to survive. The government has not helped much and he said he had only received social relief assistance from the city administration once and that had quickly disappeared.

Adam added that there were many fishermen who did not receive any assistance at all because they were not registered on the list of government assistance recipients. He suspected this was due to the failure of the local administration to renew its data on fishermen.

“Ternate fishermen have not at all been touched by assistance,” he said. “Please, the Ministry of Marine and Fishery Affair should give its attention to the regions because the current condition isn’t good at all for us.”

Current data of tuna fishermen affected by the pandemic

MDPI, an organisation that focuses its work on supporting small-scale artisanal fishing communities through conservation of fisheries resources and ecosystem in Indonesia, conducted its rapid assessment on March 20-May 5 this year to look at the impact of the pandemic on tuna fishermen such as Adam in six provinces — Moluccas, North Moluccas, East Nusa Tenggara, West Nusa Tenggara, South Sulawesi, Central Sulawesi and North Sulawesi.

The MDPI research showed that there were 117,395 fishermen in the Moluccas, 20,286 in North Moluccas, 75,850 in East Nusa Tenggara, 64,953 in West Nusa Tenggara, 154,701 in South Sulawesi, 69,476 in Central Sulawesi and 129,231 in North Sulawesi. Data collection and the assessment conducted by MDPI involved the use of questionnaires and interviewing a total of 187 fishermen who operate on full day fishing.

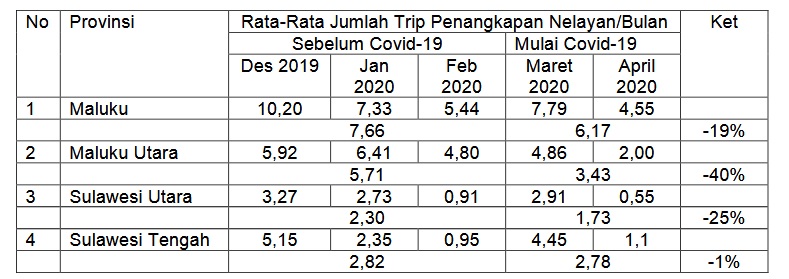

MDPI Executive Director Yasmine Simbolon said that they use boats of around one Gross Tonnage (GT) and the research showed that the number of fishing trips per month has dropped since the Covid-19 pandemic had begun to spread in the country, in early March.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted a drop in the average number of fishing trips per month for fishermen operating in the Moluccas, North Moluccas and in North Sulawesi, but not in Toli-Toli (Central Sulawesi),” Simbolon said.

The pandemic, however, did not affect the type of fish caught and Simbolon said that the day’s catches in all surveyed locations remained dominated by large tuna fish, accounting for between 50 percent and 100 percent while small tunas accounted for between zero and 41 percent.

But the pandemic has drastically driven the price of tuna down in all locations as demand from fish processing units for exports dipped. “Thus, if the Covid-19 pandemic cannot be controlled, fish prices are suspected to continue to drop,” Simbolon said.

The drop in prices however was not followed by a drop in operational costs for the traditional fishermen. There is no shortage of the diesel fuel used by the fishermen but its price remained stable.

“On average, the price of fuel before and after the start of Covid -19 here remained relatively stable or not affected,” Simbolon said.

Simbolon was also quick to point out that traditional fishermen rely on their fishing activity as the main source of income. Although, some also held side jobs as construction worker and farmer. Each fisherman has to care for a family of three to five.

Meanwhile, data from the Central Bureau of Statistics (BPS) shows there are more than 2.2 million people across the country working as fishermen in 2016.

Vulnerable economy of fishermen

Economic vulnerability refers to the risks from jolts caused by internal and external sources that affected the three key systems of the economy — production, distribution, and consumption. Simbolon said that in the context of the economy of traditional tuna fishermen, the jolts came from an external source — the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has impacted production activities in the fishery sector, mostly because of the disrupted distribution and purchase by suppliers. “The distribution disruption is because Covid-19 directly affects production activities (fishing) that are the mainstay of the livelihood of fishermen,” Simbolon said.

She added that this disruption would lead to serious social impacts if not resolved. The low demand, the high operation costs, and low fish prices all have a negative impact on the economy of the household of traditional fishermen. “If this continues it is feared that it would lead to very serious social impact on the life of fishermen’s families,” she said.

The head of the MDPI Fishery Program, Wildan Ramadhan said that negative impact of the pandemic on traditional tuna fishermen will depend greatly on global conditions. This is largely due to fishermen focusing on catching large tuna of export quality and as long as the export market remains under current condition, so will the impact on tuna fishers.

“If the pandemic continues globally, especially in the US market — as we often send (tuna) there — the impact would automatically continue,” Ramadhan said.

Government urged to increase assistance

MDPI has a number of recommendations to the government to help overcome the impacts of the pandemic on fishermen. The government must take steps to restore the prices of fish.

Ramadhan cited as an example that by controlling the distribution of fishes in the local market, tuna fishers then catch other fishes that has more stable price, to be sold in local markets.

The government could also provide incentives or ease credits for fish processing business units so that they can continue to produce and thus create demand for fish supply and helps stabilize prices.

The government also needed to subsidize fuel prices and provides assistance in the form of cash or essential goods as well as other forms of assistance to help fishermen and their family during the pandemic.

Assistance could also take the form of fishery equipment such as boats, fish catching equipment or fishing infrastructure on board ships and on land.

Djoko Arye who heads the sub-bureau for cooperation and public relations at the directorate general for fishery at the Ministry for Marine and Fishery Affairs, said that based on incoming data as of May 18, 2020, there are 294,002 fishermen impacted by COVID-19.

Arye claimed that the ministry has designed a program for impacted fishermen.

The ministry has initiated the “Bakti Nelayan” program to help the fishermen, an assistance that differed from the government’s social assistance that is distributed through the provincial administration or the local marine office.

“The assistance is in the form of essential goods and body protection equipment as well as a fish rice program in the area around fishery ports, including around the fishery port in Ternate,” said Arye.

The ministry has also submitted a proposal to the Finance Minister and the head of the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) to raise the budget of the Marine and Fishery Affairs Ministry to provide stimulus to fishermen.

Marine and Fishery Affairs Minister Edhi Prabowo, during a cabinet meeting at the end of May, has also proposed to President Joko Widodo that the government provide incentives for the marine and fishery sector a total of Rp 1.024 trillion.

Part of this funding would be used by the directorate general for fishery to carry out six programs. They are the provision of assistance for fishing at sea, fish catching equipment, 500 three-wheelers with refrigeration boxes to help deal with fish oversupply at a particular area so that the fish could be transported and sold elsewhere.

The funding would also be used to buy 500 freezer units, optimizing refueling stations for fishermen in areas where they were not yet optimal and to develop facilities in a number of ports.

When this story was published, discussions on the proposals are still underway. Ekuatorial.