Orangutans were not the only ones driven away from the fires at the Tripa peat swamp. Local residents have found the heat rising from the peatland forest unbearable.

A primate’s charred skull, no larger than a tennis ball, lay under a scorched tree. No one said anything up to that point. But as soon as Tempo attempted to lift the object, two men who had been silent were alerted. One of them, Indriyanto from the Sustainable Ecosystem non-governmental organization, immediately said: “Don’t move it. That’s evidence.”

Tripa Peat Swamp, Aceh.

Indriyanto accompanied Tempo during a trip over a week ago to the burned peat swamp forests of Tripa in Aceh. Both Indriyanto and Suratman, the local guides, were convinced that this was the skull of a baby orangutan which had perished in recent fires within the forest, which has gradually been cleared to make way for palm oil plantations. Both guides were convinced that they had seen two orangutans a few months ago in this peat swamp.

Tripa was a lush peatland forest but a permit to convert the peat swamp into plantantations changed all that. The permit had been issued to plantation company Kallista Alam by then-Aceh Governor Irwandy Yusuf. Ground checks carried out by a joint government investigation team found evidence that Tripa, home to the critically endangered orangutan, had not just been cleared out and replanted with palm oil plantations by Kallista and another palm oil company, Surya Panen Subur (SPS), it had been slashed, burned, and drained of its natural water. Fewer than 400 Sumatran tigers remain in the wild, and orangutans in Tripa have been reduced to just 200 this year.

Throughout 2011 and 2012, the Sustainable Ecosystem foundation and Aceh’s Natual Resources Conservation Agency relocated six orangutans from the Tripa peatland swamp, to a virgin forested area in Central Aceh.

It is now extremely difficult to come across a live orangutan in Tripa. As far as the eye can see, only charred trees and ash falling from those trees can be seen, with smoke still billowing out from several zones. Trekkers walking on the terrain have to use the broken trees and branches as a guide to tread on safely, or end up having one’s feet sinking into the thinning peat layers of the land. The GPS communications system proved to be quite helpful for navigation. “In the past, I used to put traps under the branches and roots, to catch catfish,” Suratman reminisced.

After crossing a 5-meter-wide canal separating the fields of Kallista and Surya, Suratman stood atop a pile of felled trees. He took out his pair of binoculars, and took a long look at the watchtower at a distance. “Empty,” Suratman said. They entered the restricted area of hundreds of hectares of plotted fields, boundaries of which were marked by the canal. In some plots, palm plantations reaching an average height of 50 centimeters could be seen.

● ● ●

LAST May, a dozen investigators from the National Police and Environment Ministry examined allegations against the managements of Kallista Alam and SPS. The focus was on two major criminal violations: use of fire to clear land, and planting on land with peat layers more than 3 meters deep. Palm oil plantation companies are the main culprit behind the destruction of the Tripa peat swamp as well as other regions in Aceh. Before they were plundered and turned into palm plantations in the 80s, the peatlands in the south western shoreline of Aceh served as sponge basins to store water. The peat swamp would absorb water during the rainy season, preventing floods, and, during the dry season, it slowly released the water, averting droughts.

The burning, building of canals on the peatland and draining today threatens to drown Tripa, as it continues to experience land subsidence every year. Such conditions cause it to flood easily.

No less important is the fact that Tripa was home to so many endangered Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii). A massive portion of Sumatra’s orangutan population live in peat swamps along the Aceh coastline where palm and rattan trees grow abundantly. The remainder are spread out in the forests within Aceh’s protected Leuser Ecosystem and the North Sumatra forests.

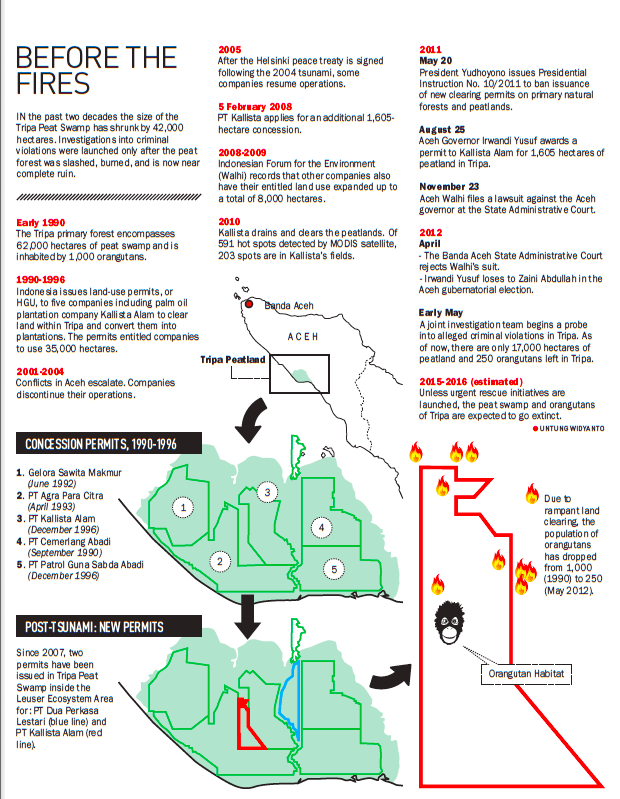

Until the early 1990s, a total of 1,000 orangutans existed across the 62,000 hectares of the Tripa peat swamp. But misfortune came in the form of land-use permits, or HGU, issued during the New Order regime to many private companies in 1991. These companies promptly converted the forests into palm plantations. There are currently seven companies holding the HGU permit to operate within Tripa, each entitled to exploit between 3,000 to 13,000 hectares, leaving only around 17,000 hectares of undisturbed peatland.

Experts on orangutans argue that the area is too small to accommodate around 280 orangutans surviving in Tripa. According to Director of the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme, Ian Singleton, a large part of the Tripa forests that burned down were the primary habitat for the orangutans. “In the past, we saw many orangutans in the area,” he said. The construction of canals and the draining have also dried up the water from the peatlands. Even if it were not burned, the vegetation providing food for the orangutans will die due to the lack of water. Referring to a study last year, Singleton estimated that the peatlands and orangutans in Rawa Tripa could be wiped out by 2015.

● ● ●

Ali Basyiah has had to spend his afternoons without a shirt in recent years. This resident of Kuala Semayam village finds the heat hard to bear. “The weather became increasingly hot since the palm plantation companies started operating here,” said Ali, whose village is located near the field managed by Kallista Alam.

According to records dated November 14, 2007, the temperature around Tripa rose drastically. It measured 37°C at 9:30am, and three hours later, it had gone up to 43°C. Five years later, Ali feels the temperature continues to rise in his village. Ali is feeling the heat not only from the rising temperature but also from the declining income from fishing. Farming and fishing activities have evaporated in the area, threatening the lives of people who depend on the forests for their food and livelihood.

Once, all he had to do to get his fish, was to place dozens of traps under the river water, and he would net around 30 kilograms of catfish and three sacks of clams at the end of each day. Such a life is long gone. At best, after painstaking hunting upstream,

Ali is able to catch just 10 kilograms of catfish a day. Director of the Aceh chapter of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), T.M. Zulfikar, said that the experience of the locals around Tripa in the past five years is quite different from the aspirations of the Aceh Green program designed by then-Governor Irwandi Yusuf, following his election in early 2007.

Based on the data, Zulfikar said that before 2007, some 20,000 hectares of forests in Aceh were destroyed annually. Since then, the number has increased to 40,000 hectares per annum. “The Aceh government does not practice what it preaches,” said Adnan N.S of the Sustainable Ecosystem’s management. ● UNTUNG WIDYANTO