The impacts of the climate crisis may force the residents of Pari Island in Thousand Islands regency out of their homes and become climate refugees.

Reachable by a two-hour boat trip from the northern coast of Jakarta, Pari Island in the Thousand Islands regency offers Jakartans a refuge from the bustling, polluted urban life, thanks to its mangrove forests and white sandy beach.

One of 112 islands in Jakarta’s only regency, Pari Island hosts a fishing community where residents not only catch fish and other marine animals as a source of livelihood but also run tourist services such as snorkeling, turning the island into a short tropical getaway for people living in Jakarta.

But the villagers are on the brink of losing their homes to the impacts of the climate crisis, through worsening tidal flooding and extreme weather.

Scientists warn that if the global temperature keeps rising beyond the safe threshold and with no ambitious climate plan from authorities, thousands of people living on small islands like Pari Island might need to seek refuge as they lose their homes to the worsening climate impacts. People on Pari Island did not have to wait to see if the climate crisis would impact them; they had experienced it in the past few years.

The latest example was in December 2021, when 53-year-old Arief Pujianto had floodwater creeping into his house; the first time such an incident had occurred after living on the island for five decades.

“At the time, the seawater reached up to my calf, deluging my refrigerator and kitchen table,” Arief said when The Jakarta Post visited Pari Island recently.

“While I didn’t have to evacuate my house, my neighbors, especially those with small children, had to move to higher ground to seek a safer place until the flood receded,” he continued.

Tidal flooding, which often occurs during a full or new moon cycle, has long been part of life for Pari Island residents. But as the climate crisis causes sea levels to rise and more extreme weather events, the flooding has become more frequent and moving further inland.

The year 2020 was the first time the island was hit by tidal flooding twice in one year, with seawater surging beyond the shoreline, according to the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi). It became worse the following year: Pari Island was hit by tidal flooding five times.

According to the environmental group, the worsening tidal flooding and rising sea levels have eroded roughly 11 percent of the 41-hectare island.

The 2021 flood forced some residents to rebuild their homes, mostly made of plywood, using bricks and cement. They also raised the foundations of their homes to make them higher than the height of the past flooding.

“If the flood was as high as that of 2021, it won’t creep into our homes anymore,” Arief said. “But who knows if the flood gets any higher in the future.” Arief also has to spend around Rp 75,000 (US$4.75) every week to buy distilled water for his daily needs, since the groundwater has been contaminated by intruding seawater.

Climate refugees

Pari Island fisherfolk, such as 52-year-old Mustaghfirin, are grappling with climate-induced extreme weather, with events getting more frequent and intense.

The unpredictable changes in wind direction make it difficult for him to catch fish, as it has altered the fish migration pattern throughout the year, leading to a significant drop in his income.

In 2020, he could still garner a daily catch of around 120 kilograms consisting of mackerel, squid and tuna during the harvest season between February and April.

“But I have yielded almost no fish in the past week,” Mutaghfirin said. “Only yesterday [Feb. 10] I got 11 kg of stingrays caught in my bubu [bamboo fish trap].”

Unless the government implements more ambitious and long-term climate solutions, Pari and other low-lying islands standing less than three meters above sea level are at a high risk of disappearing, forcing their inhabitants to move to other places and become “climate refugees”, according to Parid Ridwanuddin of Walhi.

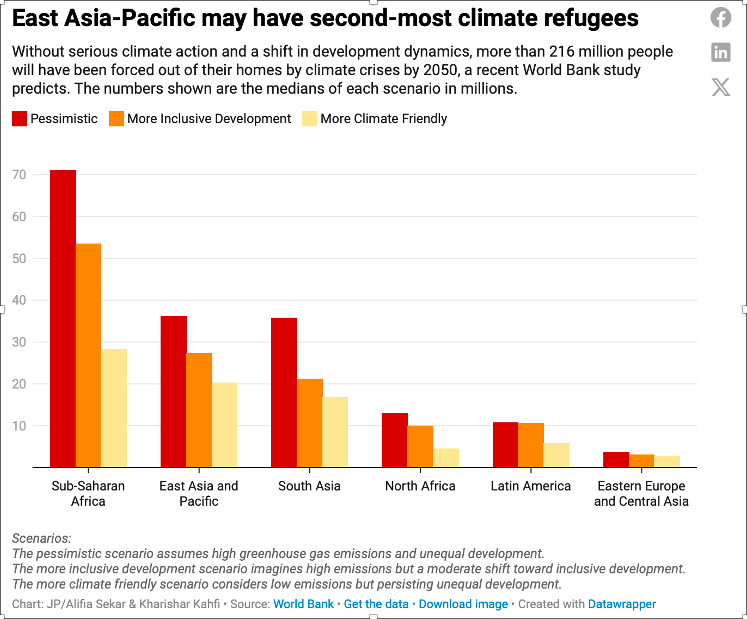

In 2021, the World Bank forecast that about 48.4 million people in East Asia and the Pacific, a region including Indonesia, could be forced from their homes by climate-related disasters by 2050 to move within their respective countries.

Such displacement can happen when people lose their homes to rising sea levels or their livelihoods due to failed harvests or droughts.

“In fact, what we call “climate refugees” have already existed since a long time ago in the Thousand Islands regency,” said Parid, who is Walhi’s campaigner on coastal and marine issues. “It just didn’t get enough attention from the government.”

He referred to the coastal communities that once lived on Ubi Besar Island, located southeast of Pari, who were forced to move in the 1950s to the neighboring Untung Jawa Island after seawater swallowed their homes and submerged the island.

As climate scientists project that the global temperature will rise above the safe threshold of 1.5 degrees Celsius before the end of the decade, Parid said it would be possible for sea levels to rise even faster and sink these small islands.

Responding to such concerns, the National Development Planning Ministry (Bappenas) is working to identify priority areas around the nation’s coastline that need immediate action. The high-risk areas include villages frequently affected by tidal flooding and coastal erosion.

“The government is also preparing a presidential instruction [Inpres] on climate resilience and special allocation funds [DAK] to finance climate actions in various regions,” Bappenas forestry and natural resources conservation director Medrilzam told the Post recently.

Redirecting policies

Researchers of the World Resources Institute (WRI) Indonesia urged the government to implement more integrated efforts between short-term solutions, such as building sea walls, and long-term ones such as planting mangrove forests and artificial coral reefs. Such efforts may help reduce the risk of tidal flooding.

“[Infrastructure] development in vulnerable areas around the shoreline also needs to be limited. What is equally important is to increase the coastal communities’ resilience in facing climate impacts,” said WRI researchers Dominika Wara Christiana and Yudhistira Satya Pribadi.

But Walhi’s Parid argued that the solutions must extend beyond technical measures, focusing instead on tackling the root causes of the climate crisis: halting more greenhouse gases from being emitted into the atmosphere.

He called authorities to shift the country’s National Long-Term Development Plan (RPJPN) away from policies that prioritize economic growth while sacrificing the environment, such as the Job Creation Law, which many saw as providing a legal avenue for environmentally destructive investments.

“What we need right now is to redirect our policies toward restoring the environment and climate,” Parid continued.

He urged policymakers to start deliberations for a bill on climate justice, which civil groups have pushed since last year. The policy would serve as a body to harmonize climate action across the country.

The Pari Island residents also refuse to go down without a fight. They are working to file a lawsuit against construction materials company Holcim at a Swiss court for its operations that are seen to be exacerbating the climate crisis.

According to the plaintiffs, as the world’s largest building materials manufacturer produced over 7 billion tonnes of carbon emission between 1950 and 2021, which is believed to have exacerbated the climate impacts, including the rising sea level that has put lives on Pari Island in jeopardy.

The plaintiffs, which are the Pari Island residents accompanied by Walhi, demand the company reduce its carbon emissions significantly and provide compensation for the residents for the climate damage they have already suffered.

“This climate litigation also sends a message to the Indonesian people that small islands are crucial for us as an archipelagic country: the sinking of one small island could mean that we’re losing our identity […] and sovereignty,” said Parid.

A Holcim spokesperson declined to comment on the lawsuit, relaying the company’s pledge to reach net-zero emissions across its value chain by 2050.

Between 2020 and 2023, the Swiss-based company claimed to have reduced its emissions by 42 percent per net sale; progress that is still within the global temperature rise threshold of 1.5 degrees C.

Mustaghfirin, who is actively working with Walhi on the lawsuit, saw the legal actions as an effort to prevent an unfavorable future: losing his home on Pari Island.

His house is in the middle of the island, so it is safe from the tidal flood, for now. But he fears that it is not impossible for the flood to reach his house in the next 10 or 20 years, especially without serious efforts to mitigate the climate crisis.

“When my house gets flooded,” Mustaghfirin said, “that is the end of Pari Island.”