CSOs believe the conservation bill must shift away from a state-centered model and actively include indigenous peoples in its creation and implementation.

“Has the management of the environment or biodiversity carried out by indigenous peoples been taught in formal schools and become a reference for those who manage our country?”

A question posed by Putu Ardana, a member of the Dalem Tamblingan indigenous people during a media briefing entitled “Views of the Civilian Society on the Draft Law on the Conservation of Natural and Bio Resources and their Ecosystem (KSDAHE)” in Jakarta on February 13, 2023.

The draft bill was initiated by the National Council of People’s Representatives (DPR RI) to replace Law No.5 of 1990 that focused on protection, Preservation, and utilization. The council and the government in mid January had already agreed on 718 items on the Problem Inventory List (DIM) and established a working committee to work on the bill.

However, the bill is considered to have not changed the state-centered conservation model when in fact, indigenous and local communities are known to have an important role in conservation. As a result, differences in perception between indigenous peoples and state officials often takes place, and unavoidable.

To bridge these differences, the civil society coalition through the Working Group Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas Indonesia (WGII) is calling on the government and lawmakers to improve the formal and material aspects of the conservation bill.

The proposed improvements are outlined in the “Policy Brief: Seven notes for improving the KSDAHE bill to strengthen the role and participation of communities in the implementation of conservation”.

“We hope that this bill will not further complicate the struggle of indigenous peoples in their rights to protect their land,” Ardana said, adding that the bill can iron out the differences in perception.

Ardana underlined the struggles that his community is facing. The Dalem Tamblingan indigenous people in Bali’s Buleleng district has proposed for the Alas Mertajati forest to be designated as a customary forest, while the government designated the area as a Nature Tourism Park.

Kasmita Widodo, coordinator of WGII Indonesia, said that the conservation bill also needs to give more authority to indigenous peoples while under the current legislation, indigenous peoples are named as conservation partners, who structurally are subordinate to the technical implementing unit (UPT) in a conservation area.

Minimizing conflicts

Data from the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN) shows there are around 1.6 million hectares (ha) of indigenous territories that overlap with conservation areas.

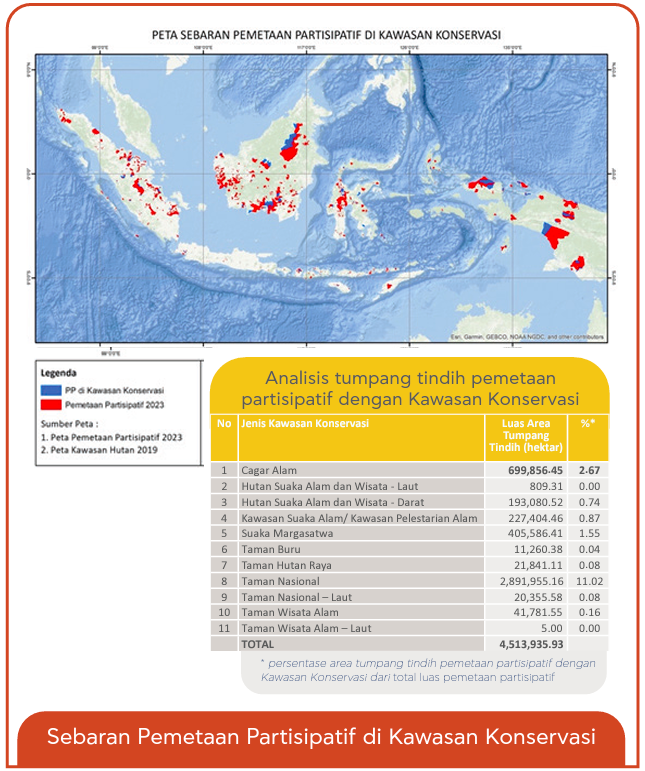

While according to the Participatory Mapping Working Network (JKPP) report, there are overlapping participatory mapping of 4.5 million ha in conservation areas, 2.9 million ha of which are in National Parks. This is one of the major issues that bill working committee is expected to address.

On land conflicts, HuMaWin — an organization that develops documenting tools — recorded that 27 of the 86 conflicts over forests occured in National parks and 13 of that those cases involved criminalization and violence.

Nadya Demadevina, research coordinator at HuMaWin believes to minimize conflicts between indigenous communities and conservation areas, it is important for the conservation bill to accommodate the opinions and interests of indigenous peoples and facilitates the recognition of indigenous territories.

Demadevina added the government often promises to accommodate indigenous rights in global forums and meetings, for example underlining indigenous peoples as a key strategy in the Forestry and Other Land Uses (FOLU) Net Sink 2030.

“The government needs the involvement of indigenous communities because the climate target of the FOLU Net Sink 2030 would be impossible to reach by merely managing supervising concessions,” she said.

However, the overlap between conservation areas and indigenous territories holds collaboration opportunities but the conservation bill must provide a balanced organizational space.

Yance Arizona, a lecturer at the Faculty of Law of Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Central Java, said that a balanced arrangement can be reached by applying the free, prior informed consent (FPIC) when determining conservation areas.

FPIC, he explained, is based on the recognition of the rights of indigenous communities to determine their own fate and needs, to respect their dignity, knowledge, and traditional way of life.

“However, the conservation bill has not considered that. Article 24, point (1) of this bill only considers the recommendations from government institutions in the field of research and the development of science and technology,” Arizona said.

Recognition of indigenous peoples

The conservation bill is expected to make peace with indigenous peoples by simplifying the recognition mechanism.

Monica Ndoen, special staff to the AMAN Secretary General said that the inventory list of problems of the bill still authorizes regional regulations (perda) to regulate the recognition of the status of indigenous peoples.

However, based on AMAN’s experience, the process of requesting recognition of indigenous peoples through local regulations takes at least 2 years. Meanwhile, AMAN members are now estimated to be around 20 million indigenous people, spread across 2,512 communities.

“There are so many beyond that (number). It is impossible for us to hope (they get recognized), there should be a regional regulation first and then can (the recognition request) be accommodated,” Ndoen said.

Arizona added, to facilitate the process of recognizing indigenous peoples, the conservation bill must transfer authorization from local regulations or regent decrees to that of the central data collection by the government.

“For example, the data collection process for the ID card. There is no need for a decree of the district head or to issue a regional regulation because all individuals are subjects of the law. So are indigenous peoples, they are already recognized in the constitution,” he explained.

In addition to actively collecting data, communities also need to be facilitated in submitting community information, potential conservation areas, and traditional knowledge. Yance said the final form of this data collection is an integrated database containing information on indigenous peoples, local wisdom, and community conservation management areas.