Medical masks have always been part of Istu Prayogi’s life since 2016, long before the Covid-19 pandemic came.

“I routinely use a mask all day long. I suffer from shortness of breath because airflow is hampered, breathing often becomes heavy, “ said Prayogi.

He was diagnosed as sensitive to air pollution. That was the first time he learned the causes of the breathing difficulties he has suffered since 1995. For two decades, Prayogi had to travel to and from hospitals without clarity on what he suffered from.

“I have undergone a CT scan, and a USG three times and had x-rays of my throat and nose taken but there were no bacteria, no virus. But my lungs, the doctor said, were crowded. They had plenty of mucus-covered spots,” said Prayogi who hails from Purworejo in Central Java.

In retrospect, the 57-year-old could now understand why he suffered headaches every late afternoon and when his nose was blocked. To alleviate the symptoms, he consumed over-the-counter medicines bought at local stalls.

“Something like clear water comes out of my nose and when this is out, I feel better and I can continue with my activity. However, as long as that has not come out yet, I cannot engage in any activity,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Prayogi worked as a teacher at five private schools around the Tanjung Barat area in South Jakarta and in Depok, West Java. He relies on his motorcycle for moving around. That means that for decades he was exposed to air pollution intensively.

He could no longer count how much money he had spent on medicine and treatments.

“A CT scan costs Rp 750,000. I remember because that was expensive and heavy in 2016. Whenever I had to travel to the hospital, my savings became depleted,” Prayogi lamented.

Unclean air contains harmful pollutants. According to the “Towards Clean Air in Jakarta” research, these pollutants include CO, NOx, SO2, and PM 2.5. The last one is the most dangerous one as Particulate Matter (PM) 2.5 measures only two to 1,5 micrometers, or 30 times thinner than human hair.

Budi Haryanto, a Professor at the Public Health Faculty of University of Indonesia, said that we automatically inhale various pollutants when we are in an environment with unclean air.

We take one breath every three seconds and exhale every three seconds. We could breathe 20 times in a minute. We cannot stop breathing, there is no alternative,” Haryanto said.

Breathing in unclean air, he said, can cause respiratory tract problems, starting with mild symptoms such as the flu or a cold.

“More serious than that, requiring a few days before symptoms appear, are lower respiratory tract problems. And then problems when it already reaches the lungs, it can take the form of shortness of breath, asthma, pneumonia or bronchitis.” Haryanto explained.

According to the Air Quality Index/AQI, in September 2022, Jakarta had the most severe air pollution, followed by Beijing, and Dhaka in Bangladesh. The PM2.5 concentration in Jakarta was 15 times over the World Health Organization safe threshold of 15 g/m3.

Motorized vehicles were the main contributors to PM 2.5 at 32-57 percent, followed by coal burning at 14 percent and construction activities at 13 percent.

Coal dust is a threat

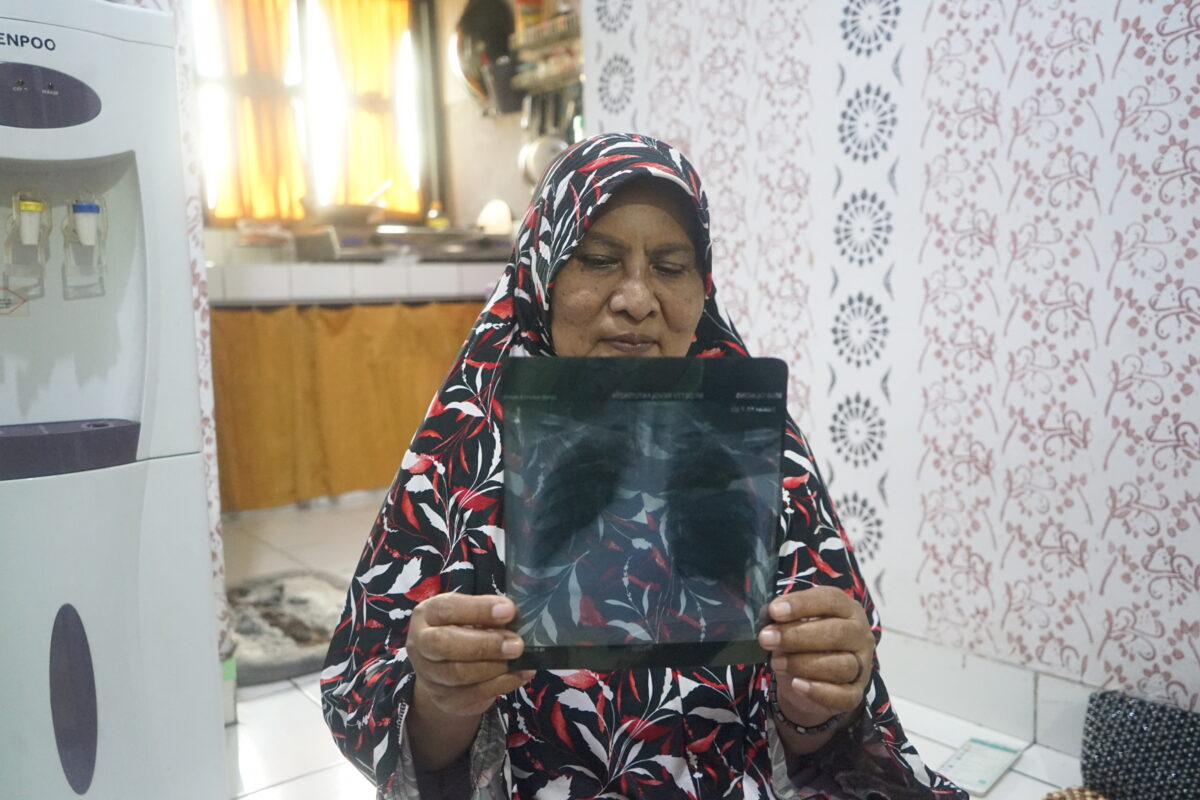

Prayogi is not the only air pollution victim. In North Jakarta, Dety Revolyatuti remembered it when coal dust hit her low-cost apartment in Marunda. In just seconds, the apartment unit she rented was covered in dark black dust.

“The dust is from 2019. Is it dust or the is sky dark? It was black and when observed, it was dark as coal,” Revolyatuti said.

The same dust was inhaled by the 65-year-old woman and this carried on for the past three years. The source of the dust is believed to be the coal loading and unloading activities of PT Karya Cipta Nusantara at Marunda Port.

“So, we are not afraid of Covid, but coal. Our white masks turn black. The floor can never be clean, every time we sweep it we get a plateful of dust. And I can no longer count the times I have had to sweep the floor,” she said.

Revolyatuti began coughing in January 2022. Her symptoms only got progressively more and worse. She finally had to seek treatment, first from the local urban ward polyclinic within the housing complex in Marunda, and then from a hospital.

“The first time it was treated, it wasn’t cured and was called bronchitis. It was really irritating and I could not sleep,” she said.

She had to change hospitals several times. First, she was examined at the Koja Hospital, then referred to the Cilincing Hospital. Revaliastuti was also diagnosed with a hernia, believed to have been caused by the cough she suffered from.

“Because when I cough, it presses my tummy, and the pressure transfers downward,” she said.

Revolyatuti then underwent surgery and is currently recovering from it. The surgery is estimated to cost dozens of million rupiah but she was luckily a beneficiary of the state health insurance scheme BPJS which covered all the costs.

“The medical costs were more than 20 million rupiah. This is a heavy sum for me who no longer has any income since my husband has passed away and my children have their own needs,” she said.

Along with the other residents of the apartment in Marunda, she urged the Jakarta government to sanction PT KCN as coal dust from its operation continued to blow into their homes.

The protest bore fruit and in June 2022, PT KCN’s environmental permit was revoked.

The visible harm

However, the success of the struggle of the residents of Marunda could not offset the harm caused by the air pollution. Most visible of all is the cost of medical treatment.

Revolyatuti said that although she did not have to shell out any money for her treatment, it was the state that had to bear the costs. The higher the number of victims like her, the more the state has to use from its state budget for something that could actually be prevented. The budget could then be used for other programs.

In the case of Prayogi, he had to bear all the costs of his medical treatment. His dream of building his own house in his village vanished as his savings were undermined by his treatment.

Haryanto said that such treatment cost was called a tangible cost.

“A tangible cost is the cost of getting sick and getting treated, purchasing our own medicine, paying doctor’s fees, etc. These are all related to his condition,” Haryanto said.

In 2010, Haryanto tried to calculate the cost of treatment for Jakarta residents suffering from air pollution-related ailments based on data from hospitals and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

The research, which is more than a decade old, came up with a fantastic sum.

“It turns out around 60 percent of the sick were linked to air pollution. the cost ranged between Rp 700 billion to Rp 38.5 trillion,” he said.

The cost would further increase if the illness caused by this air pollution was serious. These kinds of ailments can develop after exposure to pollutants for a long time.

“Heart problems, cancer, respiratory tract problems, and lower respiratory tract problems. The five top killer diseases in the world are linked to air pollution. That is why all over the world, there are real concerns about air pollution,” he said.

Ministry of Health data in 2018 showed that non-contagious air pollution-linked ailments such as heart disease cost Rp 10.5 trillion, cancer Rp 3.4 trillion, stroke Rp 2.6 trillion, chronic kidney failure Rp 2.4 trillion, Thalassemia Rp 490 billion Hemofilia Rp 358 billion, liver cirrhosis Rp 334 billion and leukemia Rp 333 billion.

Haryanto said that these tangible costs were only the least of the real costs. There are still intangible costs.

“Usually the ratio between tangible and intangible costs is between 1;1 or 1;1.5 so that if you want to see the real cost, you need to double it,” Haryanto said.

These were the costs that people like Prayogi, Revolyatuti, and the other pollution victims did not know existed.

Listen to the podcast below (in Bahasa Indonesia):

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network through the Clean Air Catalyst program, which is a flagship program launched by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and led by a global partnership of organizations including the World Resources Institute and Environmental Defense Fund and Internews. The story was first published in Indonesian on Spotify on January 9, 2023 and the online version on KBR on January 16, 2023.