Climate change and land subsidence lead to tidal floods, posing a serious problem that could submerge Pekalongan by 2035.

A wide piece of white cloth covered the lower half of 67-year-old Kartini who was sitting on a low wooden chair in her three-by-three meter living room, in the Degayu ward of Pekalongan, a city on the northern coast of Central Java.

She was entirely focused on tracing a design on the cloth with a peculiar utensil that oozed hot wax.

Canting, as it is called, is a pen with a small container filled with molten wax. Kartini carefully follows the pencil lines on the cloth and then fills a dragon depiction with dots to make its scale look lively.

”This needs patience and must be done carefully,” she said while blowing on the newly traced pattern to dry it quicker. Her right hand, holding the pen, dips into a small container sitting on a small stove, filling the pen with wax.

Together with her daughter Faizyah, Kartini (35) usually applies wax to cloth in the evenings as there are no distractions.

“Evenings are calmer, with fewer disturbances. It is easier to work then,” she said.

Batik making can be found in every corner and alley in Pekalongan. People drying batik cloth in their front yards are common sights in the city.

The website of the Pekalongan City Administration said batik production is one of the city’s economic engines. It is also the reason why Pekalongan is known as the City of Batik.

The Pekalongan City Trade, Cooperative, and SME office said that the batik industry contributed 37 percent of the city’s exports in 2021, or 26 percent up from exports in 2020.

Demand for batik has never subsided and the two women have almost no respite. They also continue to produce batiks even when Degayu, the city’s northernmost ward, is frequently visited by a long-time guest – the tidal flood.

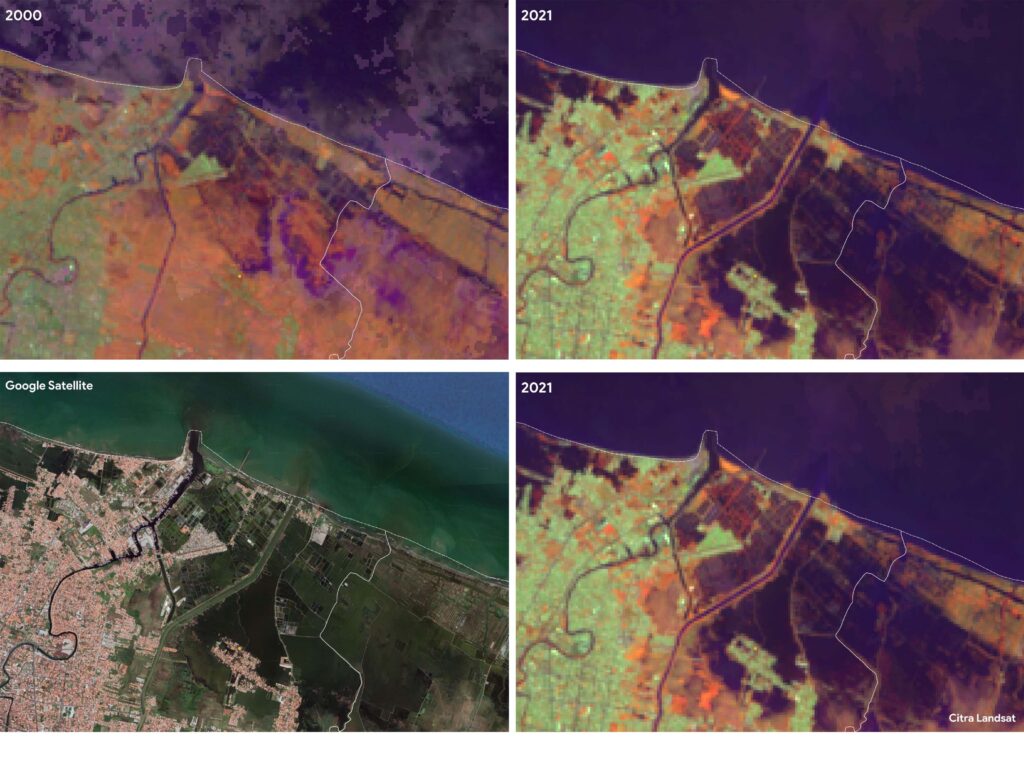

Yayasan Auriga Nusantara analysis shows significant changes to the Degayu coastline between 2000 and 2021. Early satellite imaging in 2020 showed Degayu was still untouched by seawater because the coastline was still far from settlement areas.

In 2021, satellite images (below) showed an eroded coastline and the sea covering almost 50 percent of the land in the northernmost part of Pekalongan City. Particularly in areas bordering the Batang district.

As one enters Degayu, flooding can be seen. The strong fishy and damp smell indicates this area has been submerged for a long time. On both sides of Ki Mangunsarkoro Street which borders the Gamer Ward, water can be seen submerging wide stretches of rice fields.

Sea water also covered other streets in Degayu. Yakhoni, who heads the RW98 neighborhood in Degayu said that some streets, including the one in front of Kartini and Faizyah’s home, were underwater for three consecutive years – 2019 to 2022.

In October 2022, Yakhoni had to wear tall boots to wade through the water to visit his residents. But the more serious flooding in May last year forced hundreds of people to evacuate to safer grounds from Degayu.

Faizyah, for example, had to seek temporary refuge at her parents’-in-law’s home, 10 kilometers away. “So I can continue to work. I took my batiks when I evacuated. It would be difficult for me to work if I evacuated to the ward office,” said Faizyah.

She stayed at her in-laws’ house for 40 days, until the flooding receded.

Meanwhile, Kartini chose to evacuate to the small mosque near her home. During previous floods, Kartini stayed at home, saying she felt more comfortable working from home, even though the floods restricted her movements.

“I resigned. I cried, not knowing what to do,” she recounted.

Kartini was not alone. Yakhoni said that many other residents from his neighborhood also chose to stay at their homes to continue batik making. This would not be easy when evacuating elsewhere.

***

Pekalongan has faced an annual sea level problem since 2007. Heri Andreas, a geologist from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) said that like other northern Java coastal cities, Pekalongan was also plagued by tidal floods.

He singled out two factors that made Pekalongan suffer from tidal floods – climate change and massive groundwater exploitation.

Concerning climate change, sea levels rose because the ice at the North and South Poles melted. However, this phenomenon did not have a significant impact because the sea level rose by less than one centimeter in a year.

What differentiated Pekalongan from other northern Java coastal cities was its high land subsidence rate. “It can reach more than 10 cm per year. When the land subsides while the sea level rises, the land is lower than the sea level,” he said during a discussion with Mongabay Indonesia.

Ritoni, a fish farmer in Jeruk Sari, Pekalongan, described what one would see on their walk to his pond. It was located at quite a distance from the main highway.

“The ponds were pleasant, the beach was large and if we wanted to walk to the ponds, we had to walk down the hill,” he said, recalling a time in the early 2000s.

Now, the ponds have disappeared, eaten up by the sea. Luckily, the 53-year-old still owns other ponds almost one kilometer south of his submerged ponds. The main highway which used to be quite high compared to the land around it is now no more than 50 cm above the land.

Subsidence in coastal areas is inevitable, Andreas said, explaining that this was due to the nature of coastal soil which was mostly young alluvial soil, young sediments which were softer and had a higher mineral content and thus absorbed water more easily.

Closer to the mountains inland, the soil was mostly alluvial fan soil and harder.

Java’s northern coast has soft soil. Andreas added that to make things even worse, the level of groundwater exploitation in Pekalongan is high.

The Pekalongan City Statistics Agency noted that the city’s population grew by almost 40,000 between 2000 and 2021. The latest population data for 2021 showed 308,310.

The growing population, industry, and offices lead to increasing groundwater demand as most of the city still depends on it.

Cayekti Widigdo, Head of the Pekalongan City development planning, research, and development agency said that the city needed 550 liters of water per second while the city-owned water company could only supply 150 liters per second.

“From that, only 80 (liters per second) are absorbed. There are still 70 liters per second to distribute.”

Widigdo said the main constraint lay in the water distribution network, which was still being built. A number of segments even needed to be reconstructed because they were made according to an ancient model which could not accommodate large water flow.

Besides that, surface groundwater was not always available. Widagdo added that since its establishment in 2019, the city’s water company has suffered from surface water shortages for four months every year.

“Therefore we cannot yet set a target as to when we can realize 100 percent piped water distribution for Pekalongan,” he said.

And this, he added, was one of the reasons for continuing groundwater exploitation in Pekalongan. Widagdo said that today one had to dig at least 40 meters to get solid water, not 25 meters as it used to be.

Groundwater exploitation in Pekalongan happens both illegally and legally, the latter through the community-based program that provides drinking and sanitation water in Pekalongan started in 2009.

This program was a way for the local administration to ensure drinking and sanitation water availability. Unfortunately, they also extract deep groundwater.

Pekalongan residents prefer this program because of its affordability. Kartini and Faizyah, for example, pay Rp40,000 for their water needs. The same volume would cost them Rp90,000-Rp100,000 per month if bought from the city-owned water company.

There are at least two to three providers in one village or urban ward. Andreas estimated that there are at least 400 deep wells for the program in Pekalongan.

“People are happy, but this endangers them,” Andreas said.

A study by Mercy Corps Indonesia, an organization that has a flood resilience program for Pekalongan, held together with academics from the Bogor Institute of Agriculture and the Diponegoro University, projected that rising sea levels and land subsidence would lead to the disappearance of about 5,271 hectares of land in Pekalongan City and District by 2035.

This condition means that Pekalongan will lose four times the 1,478 hectares of land it lost to the sea by 2020. The coastline is also expected to move further inland by up to 9.4 kilometers in 2035.

“From our perspective, the fact that Pekalongan City will lose 80 percent of its area by 2035 if nothing significant is done, is scary,” Denia Syam, Mercy Corps Indonesia program manager and advocacy specialist told Mongabay Indonesia.

The Pekalongan City administration is aware of climate change and land subsidence that change the landscape, but Andreas said it’s not being addressed appropriately.

During 2020, Widagdo said the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources planted six monitoring markers to measure subsidence. The results showed that the land subsided by approximately 5.7 to 5,8 centimeters in a year.

This finding is different from Andreas’ study, which found that the average land subsidence in Pekalongan is 10 cm per year. Some areas reach 15 cm-20 cm per year.

“Whatever the method and equipment used, the fact is that Pekalongan (land surface) is getting lower,” Widagdo said.

***

Land subsidence in Pekalongan, according to Widagdo, is exacerbated by rising sea levels due to climate change. “ If it was only because of the rising sea level, the impact should have been the same for the entire northern coast of Java,” he said.

Because of this, he said, the Pekalongan administration already views tidal flooding as a long-term disaster that threatens their city.

To mitigate it, they have taken three approaches: first, protecting the plains from seawater overflow, second, protecting residential areas from river overflow, and, third, building pump houses.

Cayekti said protection comes in the form of embankments and parapets. These two constructions, which are believed to be anti-tidal barriers, can be found at several points in Pekalongan city an district.

The seawalls consist of two walls 15 meters apart with a canal between them accommodating household drainage water.

When the sea overflows, it can also accommodate seawater At both ends of the seawalls are pump houses to ensure the canal water does not overflow. Any excess water is channeled into the Banger and Bremi rivers to the east and west.

Widagdo said the construction of the first such seawall in Pekalongan started on the western side in 2017 and was completed in 2019. It also connects to a seawall in the Pekalongan district.

The website of the Central Java administration said that the Rp 514 billion projects consisted of seawall development in three locations — one in Pekalongan City and two in Pekalongan District.

The massive seawall in the Pekalongan district was five kilometers long from the Siwalan sub-district to Wonokerto. It is divided in two by the Sragi River and continues to the Tirto sub-district. It connects to the North Pekalongan sub-district as well as to the Pekalongan City segment.

Parapets are walls taller than the sea or river surface. The first was built in 2015, two kilometers long from the Crematorium to Pasir Kencana Tourism Park, and completed in 2018.

A parapet was also built along major rivers such as the Loji, which was three kilometers long, and the Banger River, some 3,4 kilometers long.

Pekalongan residents said that seawalls and parapets have reduced the impacts of tidal floods. Kusriana and Muhammad Yusuf, both batik makers in the Pabean ward, 4.5 kilometers from Degayu, were among those residents.

“Floods usually are quite deep but now they do not come in (to houses). So, the seawall impact is already felt,” Kusriana said.

Prior to the seawall construction, he said seawater often flooded his home, disrupting his economic activities. Kusriana usually washes 120 batik fabrics in a week. However, when tidal floods inundated his home, he could only finish half the amount.

“After the seawall was built and the road was raised, thank God, water no longer entered our home.”

However, seawalls and parapets are only provisional solutions and Andreas said they were mere “band-aids” as land subsidence would worsen things and these temporary solutions do not address the root of the problem. The embankment and parapet, he said, will come down over time and not last.

This can be seen on the embankment that stretches from Jeruk Sari, Pekalongan District, to Kandang Panjang, Pekalongan City. Seawater has overflowed the 2.3 km long embankment several times.

On October 11, 2022, three hours after seawater overflowed, motorcycles could not pass the road.

On the same day, the parapet built along the Sragi Baru River also broke at one point. This caused substantial flooding west of the Pabean pump house in the Pekalongan district, in some areas deep enough to prevent motorized vehicles from passing through it.

Widagdo said that the parapet built near the crematorium in 2016 was also sinking fast along with the land subsidence there.

The sea was initially 15 centimeters lower than the street. The construction of the 70-centimeter high parapet brought the difference to 85 centimeters. By 2020 the difference had shrunk to just 15 centimeters.

“This means the sea level rose by 70 centimeters in just 2.5 years. Very fast,” Widagdo said.

However, the administration does not appear to have been discouraged from continuing to use this “solution,” which involves building physical infrastructure. The parapet was rebuilt in 2018 and completed in 2022.

The government is also building a seawall east of Pekalongan City since 2021. It spans from the Loji River to the Gabus River at the border with the Batang district. The work is expected to be completed this year.

So far, the central government, Pekalongan City administration, and Central Java administration have spent Rp 1.2 trillion dealing with tidal floods. The amount is expected to rise, Widagdo said.

A newly constructed parapet is in the pipeline, due to start in two to three years. He added that the seawall in Jeruk Sari is also slated to be raised in four or five years.

‘Like Heri Andreas said, this is just a band-aid,” Widagdo said.

Although the government knows these measures are only provisional and costly, it still sees them as the fastest way to deal with the problem. It was also the most visible.

Achmad Afzan Arslan Djunaid, mayor of Pekalongan told Mongabay Indonesia that tidal floods could not be tackled.

“Our mitigations are temporary at best. In fact, fighting nature is very difficult. We can prevent, not overcome,” he said.

Andreas however, had a different opinion and believed the tidal floods in Pekalongan could be addressed if there was strong will.

The most critical thing, he said, was to halt groundwater exploitation. Many cities in the world had already taken steps to achieve that.

Andreas quoted a 2013 study where Tokyo curbed groundwater use since the 60s, completely halting land subsidence a decade later.

The Thai capital Bangkok slapped high taxes on groundwater use in 1985, which slowed the city’s land subsidence.

Andreas realized that such a policy may be difficult to implement in Pekalongan. Jakarta, which dealt with the same problem, needed Rp 20 trillion to build a proper water pipeline network.

However, the sum was still cheaper than the budget to build embankments and the giant sea wall. This is estimated to amount between Rp 400 and Rp 600 trillion, he said.

“Pekalongan can do this if it really has the will. City and provincial administrations should share the same vision,” he said.

Another way to deal with the problem is to relocate the impacted communities. This is a much cheaper way according to Andreas who estimated it would cost Rp 16 trillion.

Coupled with relocation, groundwater exploitation in coastal cities should be restricted, which will slow land subsidence. The vacated settlement areas could then be converted into mangrove forests to halt erosion and rising sea levels due to climate change.

Ganjar Pranowo, Governor of Central Java, has voiced the idea of relocating climate change-affected communities. He said this when speaking at a dialogue entitled ‘The Future of Pekalongan, Consequences of Every Policy and Action’ last September.

Communication efforts to move communities, like Demak, have started. ”We are approaching the people. If they want (to relocate) we will build them houses,” Ganjar said.

For Pekalongan, Djunaidi said, a similar relocation discourse was once communicated to affected communities. “We once socialized it, but the community did not want it.”

The promotion was conducted in the Panjang, Panjang Baru, Bandengan to Pabean wards, However, the initiative dissipated as residents felt the temporary effect of the seawall built there.

On the other hand, Widagdo said, limited space is a challenge for the Pekalongan relocation plan.

Rice fields make up the majority of the remaining space. “Spatially, this cannot be converted,” he said, adding that coordination with authorities in other districts or municipalities where people could be relocated would be necessary.

There are challenges associated with the relocation plan as well. The authorities will have to ensure that those relocated have the means to make a living. “It must be ensured that they have a livelihood, access to education and health services and other things,” Widagdo said.

This report was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. It was first published in Bahasa Indonesia by Mongabay Indonesia on April 30, 2023.