Sulawesi is home to unique flora and fauna, increasingly endangered by mining and deforestation activities. Anoa, an endemic species of wild water buffalo, is on the brink of extinction. Two EJN-supported stories have pushed policymakers to establish a captive breeding center for anoa conservation

Cradled by the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, Buton is the largest island off the southeastern peninsula of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Though Buton only comprises around 3% of the total land area of the Sulawesi subregion, it is home to 62% of the area’s terrestrial birds, 42% of snakes and 33% of butterflies, according to the Opwall Biodiversity Value Report published in 2018.

Data provided by Global Forest Watch shows that Buton Island has experienced significant forest loss in its coastal areas since 2001. Buton is the nation’s only location with natural asphalt deposits, colloquially known among asphalt production companies worldwide as ‘Buton Rock’, a sought-after asphalt additive to improve durability of hot mix pavements worldwide. Southeast Sulawesi is also home to over 1.8 billion tons of nickel reserves.

This rampant deforestation driven by mining activities is endangering the unique flora and fauna of Buton Island, none more so than a small species of wild cattle called anoa, a provincial symbol endemic to the region.

With a diet that consists primarily of grasses, palm and ferns, these herbivores play a critical role in the Sulawesi ecosystem.

According to the IUCN red list, there are no more than 2,500 anoa in the world, and online reports from 2018 suggest that fewer than 300 exist in the Buton Regency in Southeast Sulawesi.

Local journalist Riza Salman recognized the urgency of the problem in 2016 and began researching and writing reports on the decline of anoa. In 2020, Salman sought support from EJN as another opportunity to report on the subject, which he felt was key to influencing the local government to prioritize anoa conservation.

“Between 2016 and 2019, I encountered challenges finding data and sources. I was able to obtain information [about the anoa] from several local studies that were conducted, but there were no definitive results. In 2020, my EJN mentor, Florence Armein, recommended sources for me to contact. That ultimately led me to authorities that were able to answer my questions.”

In 2020, Salman wrote and published two EJN-supported stories in EJN’s partner platform, the geojournalism website Ekuatorial.com: “Anoa, Masyarakat, dan Konsesi Tambang Aspal di Sekitar SM Lambusango” (Anoa, Society, and Mining Concessions around Lambusango Forest Reserve), and “Nasib Anoa di Pulau Buton Berada di Unjung Tanduk” (The Dire Fate of Buton Island’s Anoa). Both stories addressed the threats faced by the anoa and the risk of their imminent extinction.

Salman’s stories triggered responses from government officials and activists alike. The head of the Buton Regency District, La Bakry, mentioned to external researcher Reza Zaini, who contributed to EJN’s report documenting the impacts of EJN-supported stories, that anoa disappearing from Buton Island would be “a slap to our face.” La Bakry explained that such a scenario would mean that Southeast Sulawesi Province had failed to carry out the objectives of the 2013-2022 Strategic Action Plan on Anoa Conservation, a national mandate that directed each province in the Sulawesi Island Region to establish an anoa conservation area.

It was this that spurred him and other officials from various agencies such as WALHI (Southeast Sulawesi Forum for the Environment), WCS (Sulawesi Wild Conservation Society) and PKBSI, (Indonesian Zoo Association) to act.

Nearly two years after the publication of both articles, in 2022, Salman met with Berli Harli Tombili, head of the Southeast Sulawesi Tourism Office, who had major news. The southeast Sulawesi governor, Ali Mazi, had welcomed a proposal by the Kolaka District Administration to designate Padamarang Island, one of Buton’s southeast islands, an anoa breeding center.

As a person who is native to Sulawesi, I now know that there is hope for this endemic species, and hope for current and future generations.

Riza Salman

On April 5th, 2022, the Kolaka District Administration announced that they would build a conservation breeding center for anoa on neighboring Padamarang Island, which would protect anoa from being hunted, and from land clearance activities such as asphalt production and nickel mining.

A galvanized audience

Local activist Dhani Rupawan, the founder Tarsius Nature Lover Community (KPA Tarsius), a community education organization, maintains that Southeast Sulawesi Province, especially the Buton Regency, did not prioritize the 2013-2022 Strategic Action plan on anoa conservation, preferring instead to take a pro-business stance and accommodate the land use needs of the flourishing mining industry.

In fact, for many years, there was no sign that the directive would be put into effect. Then, Salman’s stories began to be circulated widely.

Salman shared his stories and met virtually with La Ode Kaida, Head of the Southeast Sulawesi Office of Natural Resource Conservation, who shared them with his network.

Prianto, a staff member at BKSDA, Indonesia’s government conservation agency, said that both stories were shared on WhatsApp groups used by government officials and soon reached wider audiences in different government sectors.

Salman’s WhatsApp exchanges with La Ode Kaida from the Kaida from Southeast Sulawesi Office of Natural Resource Conservation, who agreed to share Salman’s stories / Credit: Riza Salman

He said Salman’s stories resulted in increased cooperation between the Southeast Sulawesi Ministry of National Development Planning, the Southeast Sulawesi Office of Natural Resource Conservation, the Buton Regency, the Southeast Sulawesi Tourism Office, the Natural Resources Conservation Center (BKSDA) of Southeast Sulawesi and local NGOs.

“After this [anoa] report, we now have a sense of solidarity between different institutions,” Prianto said. The Southeast Sulawesi Office of Natural Resource Conservation and law-making institutions began to prioritize anoa conservation as part of their policies. Prianto credited the rich data presented by the EJN-supported journalist for triggering this change.

Salman’s stories, which focused on the species’ imminent extinction, sparked internal conversations among officers and encouraged the government to make a proposal for a more remote anoa breeding center.

To make the center a reality, the Southeast Sulawesi Office of Natural Conservation submitted a plan to the Southeast Sulawesi Ministry of National Development Planning, and a financial proposal to the Bappeda office, the government body responsible for approving the budget for provincial level development plans. Throughout 2021, the agency intensified pressure for a financial proposal for an anoa breeding center to be approved.

When Tombili revealed that plans for the anoa conservation center had been approved and the local government was finally moving toward breeding conservation, Salman was “beyond thrilled”.

“As a person who is native to Sulawesi, I now know that there is hope for this endemic species, and hope for current and future generations,” he said.

Though the primary use of the breeding center is to increase anoa numbers and pull the species back from the brink of extinction, Mazi, the governor of Southeast Sulawesi, hopes that the breeding center in Padamarang will become an attraction for conservation tourism, inspiring more parties to partake in anoa conservation.

Padamarang is one of the region’s seven newly appointed national strategic tourism areas and is categorized as a category V landscape by the IUCN, acknowledged to be a protected area of people and nature with significant ecological, biological and cultural value.

Belli Harli Tombili of the Southeast Sulawesi Tourism office, who shared the news about the breeding center with Salman in April, is also excited about its implications. “Through a tourism approach, we can make [anoa conservation] happen.”

At the time of publishing, Salman was unable to obtain information about the progress of the center, but he remains optimistic that there is increased political will from the local government to prioritize wildlife conservation.

A complex relationship

The anoa is the official provincial mascot and a national symbol for Sulawesi, but according to Salman, the importance of the mammal has long been overlooked and poorly understood — and its relationship with its human co-inhabitants on Buton Island is complex.

The 27,374.60-hectare Lambusango Forest Reserve, which is home to most anoa in this region, directly abuts the residents’ settlements in Lawele. Endangered by the degradation of their habitat, anoa wander into local villages with increasing regularity, where they are hunted for their meat. Anoa meat has been described as fiery, and many men believe that eating it will give them prowess and courage.

“I last got anoa about two years ago; I received 1 million and a half (rupiah) of meat per head,” Abudin, a former anoa trapper told Salman for his report ““Anoa, Masyarakat, dan Konsesi Tambang Aspal di Sekitar SM Lambusango” (Anoa, Society, and Mining Concessions around Lambusango Forest Reserve).

Anoa are also killed for foraging farmers’ crops for food. Despite their docile appearance, anoa are easily excitable and can become dangerous, particularly during breeding season. Local communities sometimes refer to anoa as referred to as ‘demons of the forest,’ as they’re known to use their sharp short horns to attack domestic cattle and other livestock.

Salman’s stories helped inspire community education and advocacy efforts to change these mindsets.

After the stories were published, the Tarsius Nature Lover Community (KPA Tarsius) began to encourage the local community to cease hunting anoa and protect its forest habitat.

“After Riza shared his article with me, I shared it with some of the community, who decided to be more involved,” said KPA Tarsius’ founder Rupawan, who sought to disseminate these messages among local villagers, especially those who might not have read Riza’s reports.

His organization helped create a community-based report system to address anoa wandering onto farms or into villages. “Two or three months ago, there was a farmer who noticed an anoa following a herd of his livestock,” Rupawan explained. “The local conservation agency received the report from this member of the community and came to safely handle and relocate the anoa.”

In recent months, KPA’s reports to the local conservation agency in the Buton Regency have steadily increased — and the reports have expanded to other wildlife, such as endemic birds and snakes as well as anoa. “The higher number of reports we have received reflects a higher conservation awareness among the community,” Rupawan said.

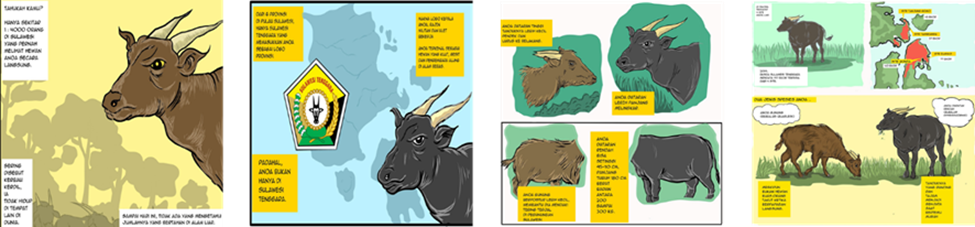

Local journalists, also inspired by Salman’s reporting, sought to make his story more accessible to communities. Komikia.id, a comic-based citizen journalist site, retold the story about the risk of anoa extinction in comic form. According to Riza, Komikia were inspired because they knew that this report had influenced the local government.

Challenges ahead

With increased community response, education and the implementation of the captive breeding center, Salman hopes that anoa can be brought back from the brink of extinction. According to the Action Plan for Anoa Conservation, its numbers would have to double to reach a minimum viable population size.

Even though his stories contributed to critical changes in attitudes and behaviors, anoas remain vulnerable.

“I still hear stories from local authorities about how people who co-habit with anoa habitat still consume the meat,” said the journalist.

Rupawan pointed out that it’s a fine balance between protecting the environment, conserving wildlife, and being mindful of people’s needs and livelihoods as well.

The very fact that wildlife is attacking them is because wildlife is threatened.

Dhani Rupawan, founder of KPA Tarsius

“Their habitat is threatened. This is why they are getting attacked, their crops are being eaten, it is because we need to take care of their habitat,” he added. “To me, [local communities] need to understand.”

The vested interests of asphalt mining industries will likely prove to be an impediment to the anoa conservation cause as well; conservation facilities cannot generate as much money as mining industries do.

Salman remains concerned about the possibility of the construction of a special Economic Zone in Buton to accommodate the mining industry. “There hasn’t been a lot of movement to prevent this from happening,” he explains. If the Economic Zone were to be implemented, it would be directly on anoa habitat. “I plan to continue to monitor this story so that I can put pressure on the government to try to find a more sustainable way of running this zone,” he says.

This report was written by Signi Livingstone-Peters and first published by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network on 31 May 2022. Impact Researcher M. Reza Zaini contributed to this report.